This post contains links to songs, please click the link below a picture to listen.

When we think of the German concentration camps of WWII, the first things that come to mind aren’t necessarily musical. And yet, Polish camp songs are some of the most beautiful and human things to have emerged. Many of the songs were sung to the melodies of classic operas, tunes that many in the camps would have known and could sing along to. But the lyrics were much more tragic, and the emotions of those held captive were poured into the music.

Music played a big part in the psychology of the experience of the camp. Each camp had its own musical establishment, an orchestra whose task it was to play while loud-speakers blared the songs around the camp while prisoners were tortured and killed. Whenever brutal punishments were to take place, interrogations involving torture, whippings or other such brutal affairs, they were to take place to a musical score. Music played when prisoners arrived to new camps gave them a false sense of security, that this camp was a hospitable place. Songs were oftentimes selected to be played because of the sadistic sentimentalism of their lyrics.

In Treblinka in 1942, the “Alley of Roses” in front of the gas chambers was where children were torn from their mothers’ arms, and the loudspeakers blasted: “Mommy, mommy, mommy- come back to me!” In 1943 and 1944 when prisoners were still being hanged in Mautthausen, the condemned were stood on the chair with the noose around their neck while the orchestra played a “farewell song”, “Come Back!” At Ravensbruck, transports full of invalids being taken to their death were loaded to the tune of a song, “Farewell”. Even when corpses were burned, carols were sung by the soldiers setting them alight.

The songs of the prisoners would seem to be a natural response to the Nazi’s perversion of music as a weapon. Instead of the fear and horror that came with hearing the orchestral scores and sentimental lyrics from loudspeakers, their own songs felt like reclaiming music, resistance and an antidote to complete despair and resignation.

Polish camp songs fell generally into two categories. The first were songs of grief, pessimism and contempt. The other category was almost the polar opposite, an attempt to turn their thoughts away from the camp atmosphere and transport their minds to happier places. Songs could conjure up a happier time, recall shared memories of home or childhood, and bring prisoners closer together. Other songs expressed strong anti-German sentiments, and these composers risked their life every time they sang. All of them rejected the present situation the prisoners found themselves in, either by looking to the past or looking to what they wished they could do.

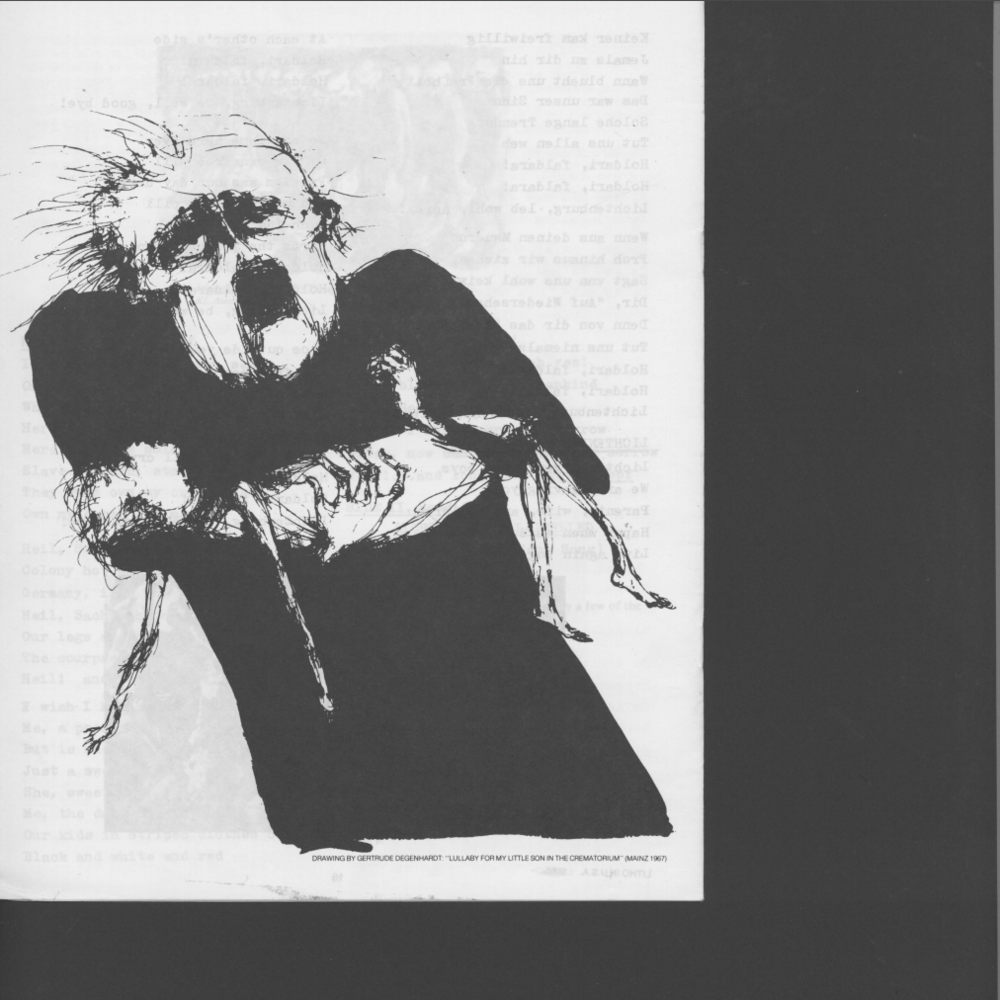

Songs had descriptive and macabre titles, such as Tango truponoszow (Tango of the Bearers of the Dead), Dicke Luft (Suffocating Air) and the title that gave me goosebumps when I first read it: Kolysanke dla synka w krematorium (Lullaby for My Little Son in the Crematorium).

“The mighty Fascist strength has fallen. The SS is lying in rubble. On their corpses and ruins we will build a new world.” –(Our Eagerly Awaited Day Has Come, Dachau, 1945)

The lyrics often mached the titles. They sang of events they witnessed, destruction and tragedy they saw, loved ones they had lost. Aaron Liebeskind in 1942 sang of his three-year-old son who had been killed: “…Your head was crushed on a cold stone wall.”

Aleksiej Sazonow, a Russian POW who was only seventeen, screamed his song as he smelled the burning of his fellow Russian prisoners, before he himself died: “A terrible pain, the fire is waiting for me. Hey! Hey! Hey! Brothers, I am blue and naked before dying…. Smoke, smoke. May it choke you, you German dogs.”

Stanislaw Roszkowski sang from his camp hospital bed: “When the smoke rises, so will I, so will I… whistle.”

In Sachsenhausen in 1942, members of the Jewish choir sand the Judische Todessang (Jewish Death Song) with the words: “Sing me a song one more time, because we must go to the gas.”

In 1943, a card was found sewn into the coat of a dead girl named Elzunia. On the card were lyrics she had written herself: “Once there was Elzunia. She was dying all alone, because her daddy is in Maidanek, and in Auschwitz her mommy…” The rest could not be read, as the words were smeared with her blood. At the bottom of the card, another child added their own writing, that they sung Elzunia’s song to the tune of “A Spark is Twinkling on the Ash Grate”.

For most in the camps, there was nothing that could be done to express their fury or pain, and so the prisoners found a small sense of comfort in tiny rebellions. Jokes amongst one another, little sabotages they knew they could get away with, telling stories, or sharing poetry and songs. The songs show their humanity, their will to live and their life experiences.

For two years now, my dear God

The Swastika has been frolicking.

No force can reign it in,

Because when you try, it’s kniebeug.

Such a frightening, huge Fuehrer,

With such a brish, that Rauber-goy

The dishwater sloshing in his noodle,

And the stupid Volk braying “Heil!”

Many authors of the lyrics began to use long-forgotten words and phrases that had subtle meanings and nuances, in a sort of protest against the vulgar speech and aggressive hate they heard throughout the camp. This was seen as an act of saving the beauty of their language from the harshness of the Nazis. Wladyslaw Kuraszkiewicz writes: “There was a language spoken in subdued tones, only in free moments, at the rest periods and on holidays, and only among close friends, as though not to shame it by dragging it through the misery of camp life- a beautiful, pure Polish which was loved with a special love, only as one can love a holy shrine. Hearing this language in the camp was like feeling the caress of a gentle breeze, like tasting food which strengthens and brings happiness.”

“How tenderly the wind caresses the birch tree. I will put your golden head to my breast. Speak to me. Whisper very quietly.” (E. Polak, Buchenwald, 1944)

Jan Tacin wrote: “It is important to stress that the treasury of camp songs consists of compositions created by people of many different nationalities who were prisoners in the camps. In the years 1945 to 1975 more than 570 songs were collected from 34 camps and sub-camps. There are also songs resulting from the uprisings in Slansk and Warsaw in November and January.”

“Bloody hands praying, praying. The accursed German womb gives birth!” – (Crucified, 1944, Sachsenhausen)

Writer Adolf Gawalewicz published in 1975 his study “Reflections in the Waiting Room on the Way to the Gas” (Cracow, 1968). In this study, he discusses the need to turn the macabre into the frivolous by using expressions and metaphors as a coping mechanism. An example of this is the comedic song with the lyrics, “Oh, it’s wonderful! There’s nothing like Auschwitz! (Nie ma jak w Oswiecimiu!, Auschwitz 1943)

Francesco Lotoro is an Italian composer who, 75 years after the war, is trying to piece together currently unrecorded musical pieces from the camps. He rescues papers from the attics and memory boxes of Holocaust victims who survived but never passed their music on. “In some cases, we are in front of masterpieces that could have changed the path of musical language in Europe if they had been written in a free world”, he says. Some of the 8,000 pieces of music he has saved were scribbled on food wrappers, telegrams or potato sacks. One was written with charcoal- given to them as a medicine for dysentery- on a piece of toilet paper and smuggled out in the camp laundry.

“Hold on to your kisser, and keep your shaved head held high…” (“Do Gory leb!”, [Hold Your Head High] KL Auschwitz, 1941)

Many of the lyrics and songs from Nazi concentration camps that we have continued knowledge of are thanks in part to two men: Joseph Kropinski and Aleksander Kulisiewicz.

Kropinski’s work was composed by candlelight in the Nazi’s pathology lab at Auschwitz, a space secured for him by other prisoners so that he had somewhere quiet to compose. Just feet from piles of bodies waiting for dismemberment, Kropinski wrote music to raise the spirits of fellow prisoners.

Aleksander Kulisiewicz was sent to Sachsenhausen in 1939 for his anti-fascist writings. He memorised the songs of hundreds of other prisoners, as well as composing his own, and after surviving the war was able to write them all down. He spent many years of his life performing these songs across Europe

“As long as you can sing and compose, and you keep it in your mind, and the SS officer doesn’t know what you keep in your mind, you are free.” – Aleksander Kulisiewicz

Leave a comment